When American mixed-media artist Faith Ringgold learned about Lucy, the ancient remains of an early human ancestor, she was so inspired that she traveled to the Ethiopian city where Lucy was found.

While on that trip, Ringgold gathered fabrics, which are part of an exhibit now on display at the Walters Art Museum titled Ethiopia at the Crossroads.

The exhibition, available to the public until March 3, places contemporary works like Ringgold’s alongside ancient African artifacts. The message is this: we all derive from Ethiopia; it is our first home. According to the museum, this is the first time in this country that an art museum has curated a show that depicts the breadth of Ethiopian art in this way.

“Ethiopia at the Crossroads is the first major art exhibition in America to examine an array of Ethiopian cultural and artistic traditions from their origins to the present day and to chart the ways in which engaging with surrounding cultures manifested in Ethiopian artistic practices,” reads the exhibition statement.

Ringgold’s Lucy: The 3.5 Million Year Old Lady (1977) is a sculpture of mixed media on wood and fabric. “The history of humankind can be traced to Ethiopia,” the museum label beneath it reads.

The artwork is an ode to Lucy. It’s a shrine featuring a miniature effigy, featuring fabric Ringgold obtained from Ethiopia, as well as items Ringgold got from her mother. This amalgamation of objects from Ringgold’s life in America and materials from Ethiopia creates a work of art that represents not only the artist’s diasporic journey but all of ours.

A fabric cut out of Africa is anchored above Lucy’s casket. On it, Ringgold has written, “Ethiopia yields oldest human fossils. Discovery said to move human origins back to four million years ago.” Next to the casket are two gold urns containing fabrics.

The exhibition was curated by Christine Sciacca, the Walters’ European art curator, and was co-organized by the Peabody Essex Museum and the Toledo Museum of Art. Ethiopian-American artist and scholar Tsedaye Makonnen was the exhibition’s guest curator of contemporary art. The Walters also invited a panel of Ethiopian community members to serve as an advisory council.

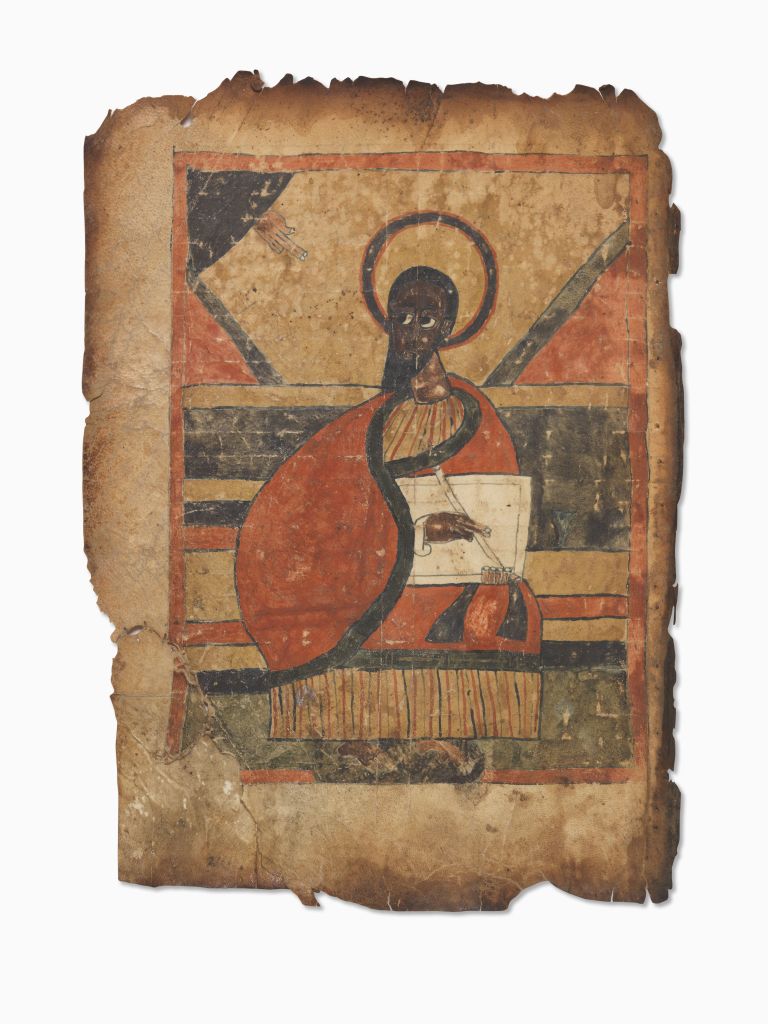

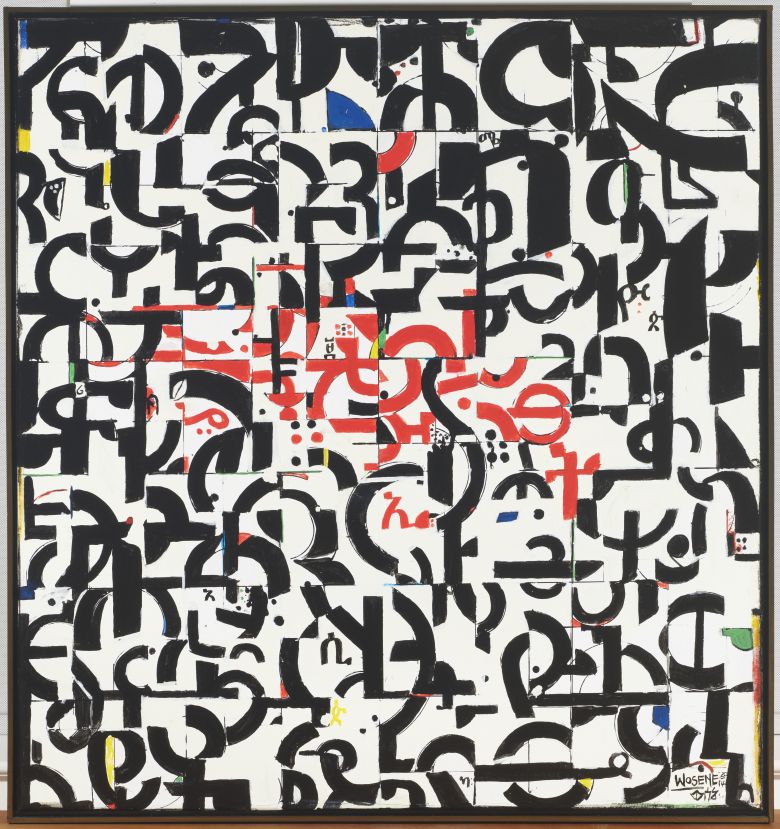

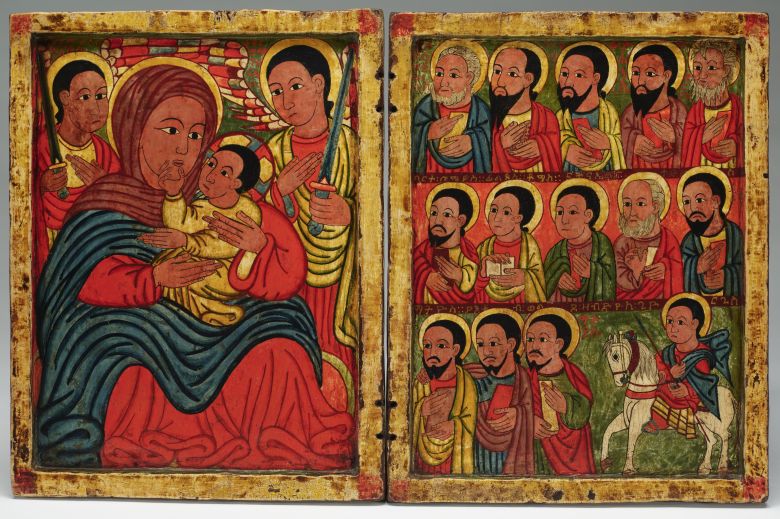

The exhibit spans nearly 2,000 years, featuring 225 historical and contemporary artworks and objects. Some of the objects are from the museum’s collection of Ethiopian art, and others are loans from other institutions and lenders.

There are woven baskets, videos, processional icons from the 16th century, ornate crosses, books, art, and other objects. For all of the traditional, more static, elements on display, some interventions allow viewers to interact with this historical exhibition in more non-traditional ways. For example, scratch-and-sniff cards that smell like berbere spice offer an olfactory experience.

The exhibition utilizes a bold color palette inspired by the Ethiopian flag, and is laid out in three distinct phases, each marked by a different color: green, yellow, or red. You might recognize that the colors of the exhibition also represent the Rastafarian flag, which regards Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie I as a foundational figure — another connection from Ethiopia to other parts of the world.

Emperor Haile Selassie I (1892-1975) was a descendant of the historic Solomonic dynasty of Ethiopian emperors, claiming lineage to King Solomon of Israel and the Queen of Sheba. Selassie was the last Ethiopian emperor and ruled between 1930 and 1974. Here, his royal cloak is on display. Magnificent black velvet, intricately adorned with gold and sequins. It’s easy to imagine the fabric draped across the leader as he reigned. Selassie owned the cloak in the 1940s; it was a gift to the Walters and has never before been displayed.

Selassie’s cloak is on view next to a work by Merikokeb Berhaunu, a painter from Addis Ababa who now lives in Silver Spring, Maryland. Her work explores the effects of a consumer society on nature. The painting Untitled XLIX (2020) looks quilted or collaged, at first glance. The artist’s layered application of paint uses muted colors that stand out against the red museum wall, representing a flower filled with cells. At the same time, the stem evokes the forms of circuit boards, a visual representation of veritable cross-pollution of nature and technology, which asks the viewer to consider the effects that we and our technology have on the environment and our decaying planet. In gazing through the vitrine that holds Selassie’s cloak, you witness Berhanu’s work, a child of Ethiopia who moved here to Maryland—a visual representation of ancestry, legacy, migration, and the diaspora.

In Theo Eshetu’s Brave New World II (1999), a multimedia and video installation, the Ethiopian artist addresses diasporic identity in an era of globalization. In it, Super 8 images of various people and places become almost indiscernible; the work is a kaleidoscope of video and mirrored panels. Brave New World II is unique in that you only recognize the depth of the work once you place yourself in conversation with it; at first glance, it seems to be simply a framed artwork. However, when you get closer, you see that it offers an optical illusion that integrates the viewer’s presence into the artwork.

According to the wall text, the work speaks primarily to the experiences of Africans on the continent and abroad. However, Eshetu’s work further represents how technology can connect disparate people and places. Many of us live far away from the places we call home, and technology provides a way to stay connected with those we love, even if they are thousands of miles away. How many of us have Facetimed a relative who lives on the other side of the world?

Two framed artworks by Helina Metaferia are on display, Headdress 6 (2019) and Headdress 23 (2021). Metaferia was born in Washington, D.C., and is the child of Ethiopian Immigrants. She is also a graduate of Morgan State University. In her collaged Headdresses series, Metaferia depicts African American women she knows personally wearing elaborate and ornate headgear that recalls the types of crowns worn historically by Ethiopian empresses.

Metaferia’s work further exemplifies the junctures that are explored throughout the show. She incorporates archival imagery from the American Civil Rights Movement. These two headdresses feature imagery drawn from Black Panther newspapers. Women with brown skin and dreadlocks peer out of the frames. Their headdresses include collaged imagery in layers includes Black Panther Party members, Black power fists raised, a crowd of protestors, orbs of gold and silver, and signs that read “Free Huey.” — another moment in the exhibition where an artwork references the past.