In 2009, the former location of Fort Worth’s oldest consecutive gay bar, The 651, reopened as the Rainbow Lounge. Just over a week later, on June 28 — the 40th anniversary of the Stonewall riots — Fort Worth police officers and agents from the Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission stormed the bar. I remember seeing news reports of the raid on TV, another instance of violence against my various intersectional identities. Officers zip-tied and arrested patrons for public intoxication, marching them into waiting paddy wagons. One young man, Chad Gibson, was thrown to the ground so roughly he suffered a head injury and bleeding in the brain. The event ignited an international controversy, leading to the creation of Fairness Fort Worth, a local activist group that successfully negotiated sweeping reforms, including changes to the city’s anti-discrimination policies and diversity training for all city officials.

Years later, when I finally visited the Rainbow Lounge, I’d been warned it might feel anticlimactic after the much fancier, shinier spaces I’d frequented in Dallas’s gayborhood, like Station 4 and Sue Ellen’s. But Rainbow felt like home. It was tiny, yet expansive in its embrace. I bumped into a high school teacher there; classmates I didn’t know were out. We exchanged looks of understanding, forming unspoken bonds. For a night, before I came out to my family, I would bloom into full embodiment on the sticky dance floor and by the wooden bar of the Rainbow Lounge in Fort Worth.

For a night, before I came out to my family, I would bloom into full embodiment on the sticky dance floor and by the wooden bar of the Rainbow Lounge in Fort Worth.

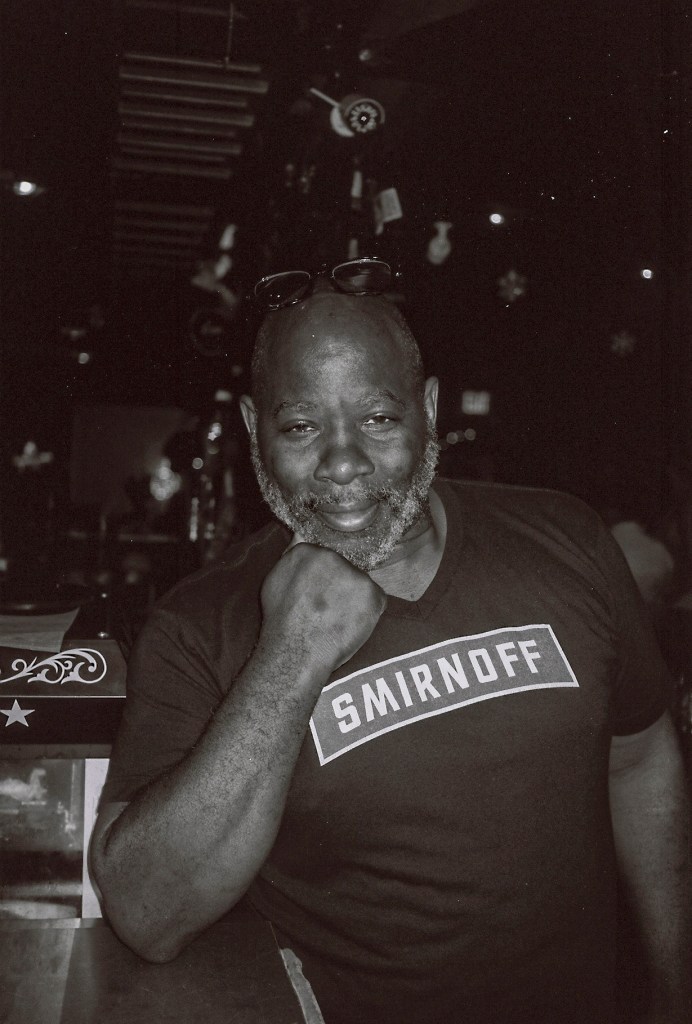

When I moved to Baltimore, I decided I wouldn’t remain in the closet any longer; I would live in my truth as a bisexual woman. It was then I met my late friend Josh, a kindred spirit and fellow club kid. I’ll never forget the day Josh introduced me to Leon’s: post-warehouse rave in some unmarked location, followed by an after-party. Josh, not ready for the night to end, suggested Leon’s of Baltimore, a space roughly the size of Rainbow, located in Mount Vernon. This was during Pride month, and he ordered me a dangerously strong vodka sunrise. (It was “morning,” after all.) From that moment, I was hooked.

After Josh passed away, I often found solace at Leon’s, visiting our favorite bartender, who had traveled with Josh. We’d share drinks, stories, and tears. These are the bonds that form chosen families, often stemming from the people you meet in those underground spaces, places where you are allowed to move freely. So many of my closest relationships are with people I met on a dance floor.

These are the bonds that form chosen families, often stemming from the people you meet in those underground spaces, places where you are allowed to move freely. So many of my closest relationships are with people I met on a dance floor.

In researching this piece, I encountered McKenzie Wark’s concept of “xeno-euphoria,” which she describes as “the ecstasy of becoming alien to oneself, riding the strangeness of the beats of techno music into somatics that are not honed into natural wholeness or a oneness but toward technological dissociation and a relational subjectivity.” This, I believe, is the most applicable definition for what I mean when I say dance floors and queer spaces are incubators for folks to “lose themselves.” It’s not about disappearance, but about becoming part of a moment where others are also seeking connection, facilitated by the music.

These people, my chosen family, and these structures — from Rainbow in Fort Worth to Leon’s in Baltimore — are “third places.” They are sanctuaries where folks on the fringe of society — the marginalized — can congregate, find community, and locate kinship.

They’re where people flirt, fall in love, fight, order rounds of shots, lose their keys, stumble, place dirty coins in jukeboxes, or queue up TouchTunes. With each of these small, communal acts, we affirm that we are alive.

They’re where people flirt, fall in love, fight, order rounds of shots, lose their keys, stumble, place dirty coins in jukeboxes, or queue up TouchTunes. With each of these small, communal acts, we affirm that we are alive.

This historical context makes the ongoing loss of physical spaces, such as the demolition of Grand Central — a beloved nightclub that was destroyed in 2021 by developers Landmark Partners — particularly resonant. When I first moved to Baltimore in 2016, Google searches for neighborhoods within walking distance of my school consistently pointed to Mount Vernon, lauded as “the gayborhood.” Yet, in my time here, I’ve witnessed countless brick-and-mortar queer spaces close their doors due to a global pandemic, rising rents, and gentrification. Sanchez Sanders, who transitioned to bartending during COVID after a career as a chef, observes the challenges Mount Vernon faces.

“I think COVID was a big part of it, and the lack of foot traffic, lack of retail and grocery, the theft and vandalism as well,” he said.

Despite these closures, dance floors — whether in established clubs, temporary party spaces, or bars like Leon’s — have always been, and must continue to be, places of rapture and refuge.

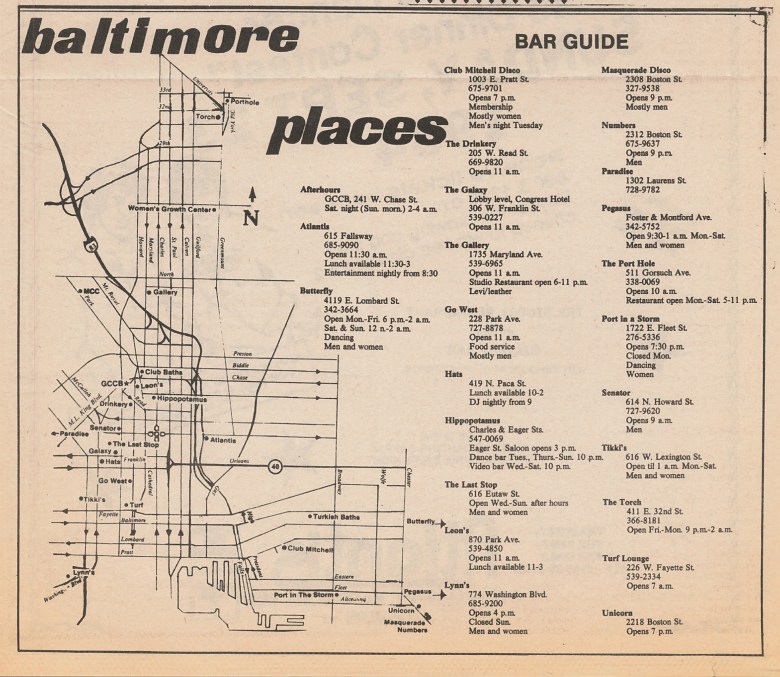

Iconic brick-and-mortar spaces like the Gallery Bar, The Hippo, The Paradox, and Grand Central, along with those like O’Dell’s before my time, served as havens for survival, both spiritually and physically. What does it mean when these vital anchors of community are gone?

Iconic brick-and-mortar spaces like the Gallery Bar, The Hippo, The Paradox, and Grand Central, along with those like O’Dell’s before my time, served as havens for survival, both spiritually and physically. What does it mean when these vital anchors of community are gone?

These losses mean the roles that music and joyful queer expression play in creating and maintaining community and resistance are even more critical. We find sanctuary when we have the freedom to be enmeshed in our countercultures. In this current political and social landscape, we long for the dancefloor, just as we ached during the pandemic lockdown to be in community again — under neon lights, the creep of fog, and the sweaty amalgamation of a grinding crowd. We long for a place to sit and have a drink with dignity, to meet a cute stranger, to not feel alien, to perhaps muster up the courage to sing karaoke.

For queer folks, dancefloors, raves, drag watch nights, karaoke, and parties have become churches; they serve as sanctuaries. It’s not too cliché to draw parallels between religious ecstasy and the ecstasy felt on a dancefloor, where time collapses and differences dissolve. Here, music becomes a conduit for expression, connection, and radical joy in the face of oppression. These moments were critically necessary 50 years ago, and they remain so.

This vibrant community spirit — and the creation of third places — is actively nurtured by the people at the heart of these establishments. At Leon’s, figures like bartender Sanders and entertainment host Stacey Antoine are pivotal in shaping the experience. Sanders, with his Southern Baptist roots and family ties to Cameroon and Panama, believes, “bartenders set the tone.” He sees a diverse clientele, from out-of-town visitors to local regulars who range from age 21 to 70-plus, and makes it a point to ensure comfort and safety. He recalls a memorable moment with a guest who had just come out and was concerned about how he would be perceived in the community. “I told him, ‘If you want to meet people, don’t be scared. Have confidence,’” Sanders told me. This ethos of care is crucial in a world that often lacks it.

Writer and cultural theorist DeForrest Brown Jr.’s notion of “world-building” powerfully resonates with the way Baltimore’s LGBTQ hosts, bartenders, and emcees use music to transform spaces into havens. Dancefloors and karaoke nights offer both escape and embodiment in a terrifying and dangerous world that often seeks to erase and minimize us. This year, as Baltimore City Pride celebrates its 50th anniversary, the significance of these spaces — like Leon’s Backroom — remains paramount. My first memories of Pride — of true embodiment and true freedom — were found within these queer spaces.

Two years ago, I learned that my beloved Rainbow Lounge burned down in a fire on June 1, 2017. The loss of such a vital space in Fort Worth underscores the preciousness of enduring establishments like Leon’s, which holds the distinction of being Maryland’s oldest continuously gay bar, a testament to its resilience and the unwavering need for such sanctuaries. Stacey Antoine sees this endurance as vital.

“Being that it’s one of only a handful of gay bars in the city that’s still standing and has zero chance of closing anytime soon, I’d say it’s vital to the community for every reason,” he said. Sanders echoes this sentiment with hope for the future.

“It’s a local bar and it has been around for a long time. I think we are on the right trajectory to be around for another 50 years.”

According to Antoine, the key to this incredible longevity is that Leon’s doesn’t over complicate things. It’s affordable and it’s dependable. It also adapts when it needs to. As evidence, he points to the success of the revamped Miss Leon’s pageant and the popular monthly drag show, “Karmella and the Shady Ladies.”

Nowhere is Leon’s welcoming energy and world-building more palpable than during its renowned karaoke nights, hosted three nights a week by the dynamic Stacey Antoine, with Sanders or another of Leon’s dedicated bartenders. If you go to Leon’s karaoke, be prepared to sing, but don’t feel intimidated. Originally from Harford County, Antoine has been honing his craft at Leon’s for nearly four years after moving his show from the former Grand Central Nightclub. He cultivates an atmosphere he describes as “pretty crowded, fun, and filled with eclectic talent.”

The crowd is hilarious, jovial, intergenerational, queer, and incredibly supportive of every effort, largely thanks to Stacey Antoine’s encouragement.

“I tell people all the time: ‘It’s just karaoke. It ain’t the Meyerhoff,’” he laughs. “‘I won’t force you on stage. You can sing from your seat. And don’t mind the audience. They aint nobody!’”

It creates truly special moments, like when he kept karaoke going for a small group celebrating a marriage on a pre-wedding night out when the rest of the city was dead. “They ended up having a blast and were very thankful,” Stacey Antoine recalls. “It was a really touching moment for them and I was just glad to be a part of their evening.”

It’s in these moments, and in the cheers for every singer, that the spirit of Leon’s truly shines, offering, as Stacey Antoine hopes, a place to “support, uplift, entertain, welcome, and provide a safe space for our LGBTQIA+ community.” Or, as he’d simply put it to a newcomer: “Come on out and have a gay ‘ol time with us and drink and sing a spell!”