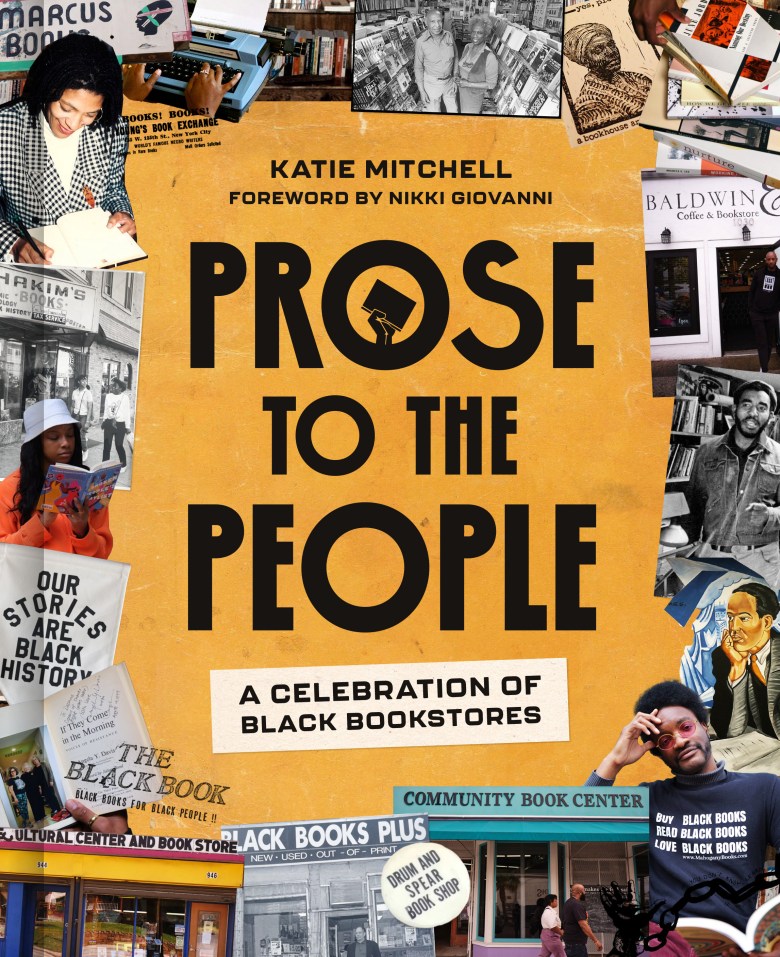

Katie Mitchell of Atlanta, Georgia, is a writer, reader, and researcher whose online bookshop Good Books ATL offers vintage and contemporary reads from Black authors. As of last month, Mitchell is the author of her first book titled, “Prose to the People: A Celebration of Black Bookstores.” In March, I had the opportunity to speak with Mitchell about the book’s genesis, her travels, and the recurring themes throughout the text that allude to a larger history of surveillance for Black communities. “Prose” is a chronicle of Black bookstore history that guides us through time and space. My favorite moments from the book are the pages spent exploring the life and memory of Martin Sostre, a political prisoner who committed his life to literacy and the liberation of Black people all over the world. May this interview encourage us all to keep reading.

Bry Reed: To start, let’s talk about how “Prose” went from idea to reality. What sparked that transformation?

Katie Mitchell: I was in Washington D.C., and I was looking for Black bookstores. I eventually found one, and the person working there gave me some great recommendations. That night, I wrote in my journal: “a book about Black bookstores.” I had this idea that I wanted [the book] to be like a Black bookstore. What I mean by that is, I wanted it to have a diversity of thought. I wanted it to be highly visual. I wanted it to feature a lot of different media. And I wanted it to be very engaging, like how I find Black bookstores to be.

I think “Prose” goes beyond what I originally wrote down. It’s an anthology. You hear from Nikki Giovanni, Kiese Laymon, Rio Cortez — so many great people. There’s poetry, there’s essays, and there’s interviews. I wanted “Prose” to encompass the feeling of Black bookstores, and I wanted people to be able to experience the [Black] bookstores that no longer exist. You’ll see pictures of those places and you’ll get interviews from people who were in them. You get to see all of that in “Prose.”

BR: The book features a foreword from the late and great Nikki Giovanni. Did that connection happen through the publishing house or was she someone you had a personal connection to?

KM: Nikki Giovanni is one of those people you know of your whole life, so you feel like you know them. I met her at a couple of signings, but when I was recording the book, every bookstore that was around from the ‘60s to the early 2000s had a Nikki Giovanni story. And they were all positive! She’s such a big writer that when these Black bookstores would get her [to do readings], it’d propel their store to a national level. She was really helping these bookstores out. She could’ve gone to chain bookstores, but she went [to local Black bookstores]. Everyone had a great story about her, and that’s when I thought that I’d really like her to have the first word in “Prose to the People.” I think she deserved that.

BR: As you were on the journey of collecting these stories and experiences for the book, how did it feel to be able to hear from these independent booksellers?

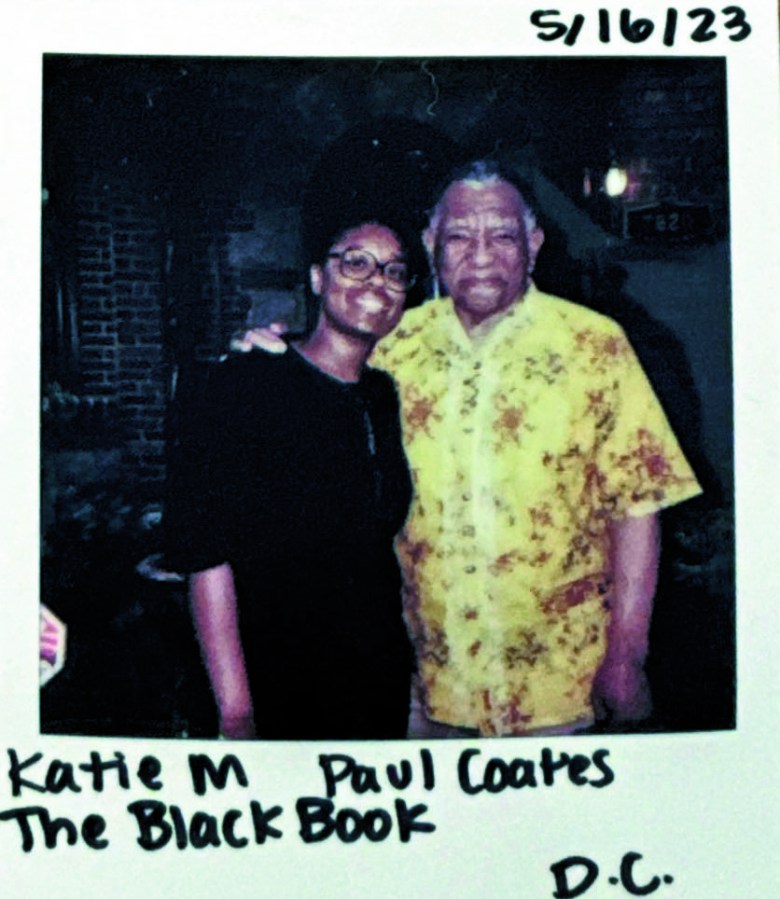

KM: It was something that I felt a weight to. I knew there hadn’t been a book like this before, and I knew it was really important. One of the unexpected things that came about was how many older friends I’d make because of this book. I’ve been hanging out with all these octogenarians who tell me about their bookstores and the civil rights movement and all this great stuff that I wouldn’t have known if it wasn’t for “Prose.” Now, all of my best friends are in their 80s.

BR: You also do a great job of giving us a bookseller and bookstore historiography. How did it feel to compile these stories and see those connections playing out through storytelling?

Courtesy of Katie Mitchell.

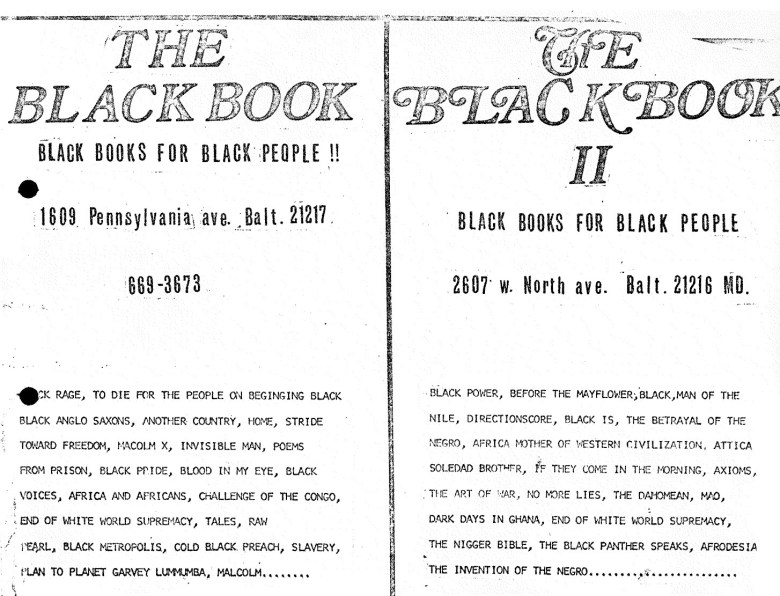

KM: To me, it feels like a big family tree. Pick any story and you can trace it back to the National Memorial African Bookstore. Paul Coates, Ta-Nehisi’s dad, who had The Black Book bookstore, went there to get books, and then Ta-Nehisi was at Everyone’s Place bookstore, where he had his first signing. Then Everyone’s Place helped out Sankofa Video, Books & Cafe. There are so many connections. When people think of business, they tend to think that these [booksellers] are in strict business with each other. To some extent, they are competing for customers — even more so now, in the internet age — but they were actually helping each other. When The Liberation Bookstore closed, they gave the rest of their inventory to the Hueman Books when it came to Harlem. There are all these connections. It’s something that you wouldn’t truly get until you’re in the archives and pulling [those layers] back.

BR: I was really intrigued, as a Baltimore native, to see you reference The AFRO archives. Did you have an opportunity to work with the team at AFRO Charities?

KM: Yeah! AFRO Charities were the ones who got me that picture of W.E.B. Du Bois at the Hugh Gordon Bookshop. They were great! It’s another one of those serendipitous connections.

BR: Through these auxiliary essays (and citations) you see these different images that you’ve pulled from the FBI, CIA, and COINTELPRO archives. Did you expect that pattern of surveillance to emerge when you first had the idea to chronicle the history of Black bookstores?

KM: I knew it’d be a theme, although I didn’t know to what extent. Being in the archives, I realized that the FBI probably has the most complete archive of Black bookstores because they were being surveilled so much. A lot of the ephemera that Black bookstores have probably wouldn’t be around if the FBI hadn’t archived it. It’s kinda like great that I get to see this flyer about the Black bookstore George Jackson movement. However, the reason I get to see it is because [these stores] were getting spied on!

BR: As “Prose” came together, what was it like to chronicle the histories of physical spaces? What was it like to witness the ways communities are changed by the decisions of people in power?

KM: You think of gentrification as a new phenomenon like “Ugh! The rent is so high in Atlanta and I can’t afford a house in D.C.” Then you look back at the ‘60s and ‘70s and realize that [people in power] were kicking us out for a long time. It’d be called “urban renewal,” or as James Baldwin said “negro removal”. It’s interesting because sometimes they’d demolish these buildings, say they were building something, and then nothing would get built.

I think that in addition to the surveillance that the government did, the fact that they were physically demolishing these spaces shows the kind of threat [Black] bookstores were to government officials. It was like “This time, we aren’t going to shoot you or put a bomb in your car, but we’re going to demolish [this building], and we know you’re not going to be able to find another space.” This happened so many times, and not just in the South. There were a good four or five bookstores in Harlem that all had the same fate because of one state office building.

BR: To shift gears a bit from surveillance, I want to talk about your childhood. Where did young Katie find stories that called to her?

KM: My mother would be the person I have to credit for helping me find those stories. She was like “Y’all are reading these Black books, and before you go outside to play, you need to recite this poem and do it perfectly.” She was the one who introduced me to that world. And by my late elementary school years, I was reading adult books alongside her. She introduced me to a love for Black literature, but also a love for Black people and the love of self. I never had an identity crisis of [thinking] Black people aren’t good enough. I think that was because my mom instilled those values into me early.

BR: What’s one thing you hope readers take from your new book?

KM: I’d love for people to know that you can be in your own community and not know what was there before. Things can change so quickly, and as we get further [removed] from the time [they were around], there’s less people who remember them. I want “Prose” to be an aid to remembering.

“I’d love for people to know that you can be in your own community and not know what was there before. Things can change so quickly, and as we get further [removed] from the time [they were around], there’s less people who remember them. I want “Prose” to be an aid to remembering.”

Katie Mitchell, author of “prose to the people: a celebration of black bookstores”

—

Prose to the People is available at local libraries and bookstores.