The Enoch Pratt Free Library held its 37th annual Booklovers’ Breakfast at the Baltimore Marriott Waterfront on February 1, marking the beginning of Black History Month programming for one of the oldest public library systems in the United States. This annual event brings together hundreds of book club members, library enthusiasts, and community members from across the mid-Atlantic to Baltimore City to celebrate literacy and learn about the Pratt’s plans for the upcoming year.

As in previous years, this gathering also serves as an opportunity to assess the state of libraries in the United States. In 2025, many public library systems nationwide are facing challenges such as threats of defunding, restrictive book bans, and declining circulation rates, which are concerning to advocates of library services.

One constant presence at the Booklovers’ Breakfast is Oxon Hill, Maryland-based Mahogany Books. The family-run, Black-owned bookstore is the official bookselling partner of the event, and owners Ramunda and Derrick Young champion literacy as a part of Black storytelling. When asked how it feels to attend the event every year, Ramunda Young is clear: “It is crucial for us to be here. We must be wherever Black books are being celebrated.”

“Our hope is that attendees continue to fall in love with our stories. It’s important that Black stories are passed down from generation to generation,” Ramunda Young said.

Another attendee Ryah Bunting, founder of the Cut and Discussed book club, is a Baltimore native excited about the annual Booklovers’ event since attending for the first time last year. Bunting says the onus for starting her book club was very personal, “I love food. I have a massive library and wanted accountability for reading all the books I have.” Since beginning the book club with her younger sister and grandmother, she’s gotten to know many new people of all genders and across personal interests. Bunting, a Howard University alum, is a big proponent of book clubs’ ability to gather people.

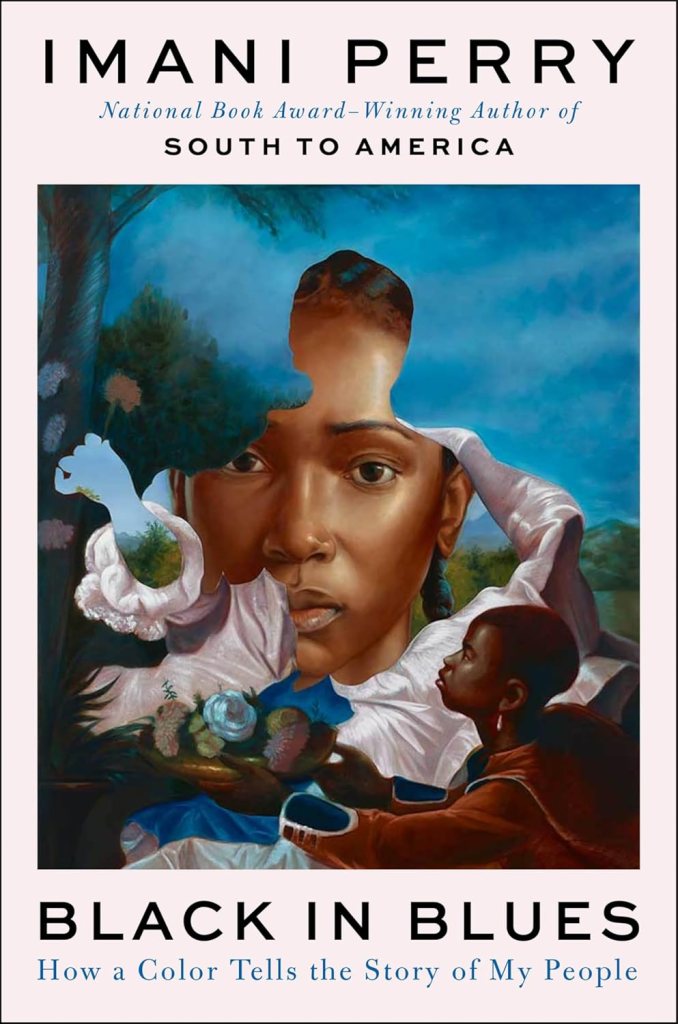

This year’s keynote speaker, Imani Perry, is one scholar striving to share Black history across generations. For this year’s event, she delivered a lecture connecting her latest book, “Black in Blues: How a Color Tells the Story of My People,” with the long arc of Black resistance movements that she believes offer guidance for surviving the present.

In her 2022 acceptance speech for the National Book Awards’ Nonfiction Book of the Year award, Perry said, “I’m sweetly indebted and deeply bound to my family and friends from Birmingham, Boston, Philly, Chicago, Milwaukee, Georgia, Tennessee, Los Angeles, New Orleans, and always Mississippi: land of the bluest blues.” With the publication of her latest book, “Black in Blues,” Perry’s fans can read about the bluest blues of Mississippi, along with the multilayered history of how blues — as a color, genre, and mood — fasten to Black life.

In addition to being a National Book Award winner, Perry is the Henry A. Morss, Jr. and Elizabeth W. Morss Professor of Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality and of African and African American Studies at Harvard University. She previously taught at Princeton University and has published several other monographs, including “Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry” (2018) and “May We Forever Stand: A History of the Black National Anthem” (2018). In 2023, Perry was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship, also known as a “genius grant,” for her interdisciplinary scholarship.

The moments before Perry takes the stage are anticipatory. I, along with other attendees, the Pratt team, and hotel staff rotate around the venue, navigating the aisles between round, navy blue breakfast tables. Plates, mugs, and books overflow atop the dark linen cloth as conversation about Perry’s past work, The Pratt’s upcoming events, and other topics fill the space.

“Have you read the latest work?” I overhear from across the table. A pause and then a chuckle precedes the response, “I haven’t even started.” The air is light, and copies of Perry’s work are scattered around nearly every surface.

Before the keynote begins, Chad Helton, the new president and CEO of the Enoch Pratt Library, opens the event with a message of gratitude for all the attendees and staff members who make the annual event a success. The welcome concludes with a roll call of the book clubs in attendance and a lively invitation for attendees to applaud themselves and their peers for their commitment to literacy and community.

Afterward, Perry takes the stage in a long-sleeved dress that lands between cobalt and indigo. The curtains behind her are Oxford blue. Before a word is spoken, the ballroom’s visual tone — the curtains, tablecloths, and other linens — adds to the thematic refrain of the lecture. We are here to discuss the blues and its meaning across history for African Americans. Perry’s opening of “Happy Black History Month!” is met with applause before she acknowledges the bittersweet triumph of the phrase: the federal government’s current crusade against the very meaning of our gathering. She proceeds to declare, “The federal government didn’t give us Black History Month and cannot take it away.” The audience erupts. Clapping, hollering, and the sound of a reassured public answer her.

From then on, Perry’s keynote transforms into an interrogative lecture about the history of the blues as a focal point of Black life, organizing, and art deserving of rigorous study. Through her analysis of Rayford Logan’s book, “The Betrayal of the Negro” (1965), and Alain Locke’s 1925 essay, “Enter the New Negro,” Perry asserts that lessons from the past are integral to our collective survival against state tyranny.

From then on, Perry’s keynote transforms into an interrogative lecture about the history of the blues as a focal point of Black life, organizing, and art deserving of rigorous study. Through her analysis of Rayford Logan’s book, “The Betrayal of the Negro” (1965), and Alain Locke’s 1925 essay, “Enter the New Negro,” Perry asserts that lessons from the past are integral to our collective survival against state tyranny.

“The efforts made at the lowest points [of Black suffering] made the gains of the Civil Rights Movement possible,” Perry says. Her statement is followed by a recollection of the historic conditions that birthed “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” written by James Weldon Johnson and set to music composed by his brother J. Rosamond Johnson in 1900.

“The efforts made at the lowest points [of Black suffering] made the gains of the Civil Rights Movement possible,” Perry says. Her statement is followed by a recollection of the historic conditions that birthed “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” written by James Weldon Johnson and set to music composed by his brother J. Rosamond Johnson in 1900.

Perry draws on the work of Albert Murray and his 1971 memoir, “South to a Very Old Place,” to emphasize that “Lift Every Voice and Sing” began as a “school bell song” for Black Southern children at the turn of the 20th century, preceding the codification of any song as a U.S. national anthem. To be clear, “The Star Spangled Banner,” written by Francis Scott Key in Baltimore in 1814, was not adopted as the official anthem of the United States until 1931 by President Herbert Hoover. Therefore, it remains true that before the State recognized any anthem, there was widespread community support from Black educators and students, from Alabama to the Carolinas, for a schoolyard song that would change the nation. Perry’s opening is a well-researched reminder that one of the greatest musical artifacts of the 20th century began with Black Southern peoples’ pursuit of quality, culturally-resonant art to reinforce the lessons being taught to their children in schoolhouses.

As her lecture continues, Perry reminds us that now “is the time to be instructed in the practice of creating beauty at the site of need.” Though we all sit in a hotel ballroom yards away from the Inner Harbor, Perry’s words transform the space into a lively classroom. For the next hour, we are students.

With each passing minute, Perry fashions a multilayered historiography of Black life and its tethering to the blues. We are reminded that those in bondage in the 17th century (and onward) “were being sold for blocks of indigo” and prompted to consider, “What did people see when they were being thrown over the board of the slave ship?” as she helps us understand the depth of blues in Black history. Then, Perry stitches together a broad timeline by citing scholars and artists throughout history as pieces of her epic quilt. Concurrently, Perry advises the audience not to dismiss today’s repressive political leaders. She cautions against labeling them as monsters, stating plainly, “They must be treated as humans who’ve betrayed their greatest virtues.”

Perry’s advice is practical and strategic. In her delivery, she stresses the idea that our country enters periods of repression following failures in ethics. “We are still tasked in adversity to make a living future,” Perry asserts. Her fundamental belief is that the past provides “an ethical foundation for what we carry in the present.” In Perry’s assessment, dismissing ethical failures as actions of inhuman enemies — instead of the measured choices of those who are committed to political violence — is a misstep. Instead of monstrosity, those failures are the culmination of miseducation that Perry suggests is only remedied by a devotion to “haunting the past.”

Her answer is returning to lessons of those who survived by focusing “on what Black people had done internally to their communities” to make it through the “thicket of segregation.” She’s calling our attention to “the beauty of people who sang the blues when they had the worst blues of all.” Perry is referring to the Nadir.

By definition, the Nadir means the lowest point in an astronomical horizon. It’s the bottom. The Nadir Perry references here is a historical period. From 1890 to 1940, Africans/African Americans in the United States endured unrelenting racial terror known as The Nadir. Events like Red Summer in 1919 and the ongoing slaughter of Black people via lynchings are some of the acts of violence marking the era immediately following the political gains of Black communities in Reconstruction. Perry calls on us to learn from the archives and communal histories available as necessary guides for our present survival. “Continue the tradition of educating young people even when it’s fugitive” is her marching order. She says, “Open living rooms to have conversations if we can’t have them in public anymore.” Her words echo the writing and pedagogical work of the late June Jordan whose work on “Life Studies” often contended with living rooms as sites of education and conversation about all things needed for dignified lives.

With the assessment of the Nadir, Perry goes on to highlight the agricultural and artistic work of George Washington Carver at Tuskegee University. She spans a long history of agricultural development and artistic marvels to emphasize that during a period of fatal losses, Carver worked with Alabamans to survive. The knowledge gained from his work with farmers in Alabama led Carver to magnificent discoveries, like the first recreation of rare Egyptian Blue containing pigments derived from Alabama soil in his lab. Carver’s legacy as a brilliant polymath is coupled with another major figure in Black in Blues: Lorna Simpson. If the Nadir is an astronomical low, then the zenith is the high, and Simpson’s artwork is evidence in the American Jeremiah (prophecy). Perry draws together the history of Carver’s marvelous Egyptian Blue with Lorna Simpson’s bluestone pigment from quarries in upstate New York. Both are roadmaps.

Perry closes her lecture with the sobering statement, “Society will be lost if we don’t change our course.” She draws again upon the histories of Harriet Jacobs and Gil Scott-Heron, a self-proclaimed blueologist, as tools for surviving.