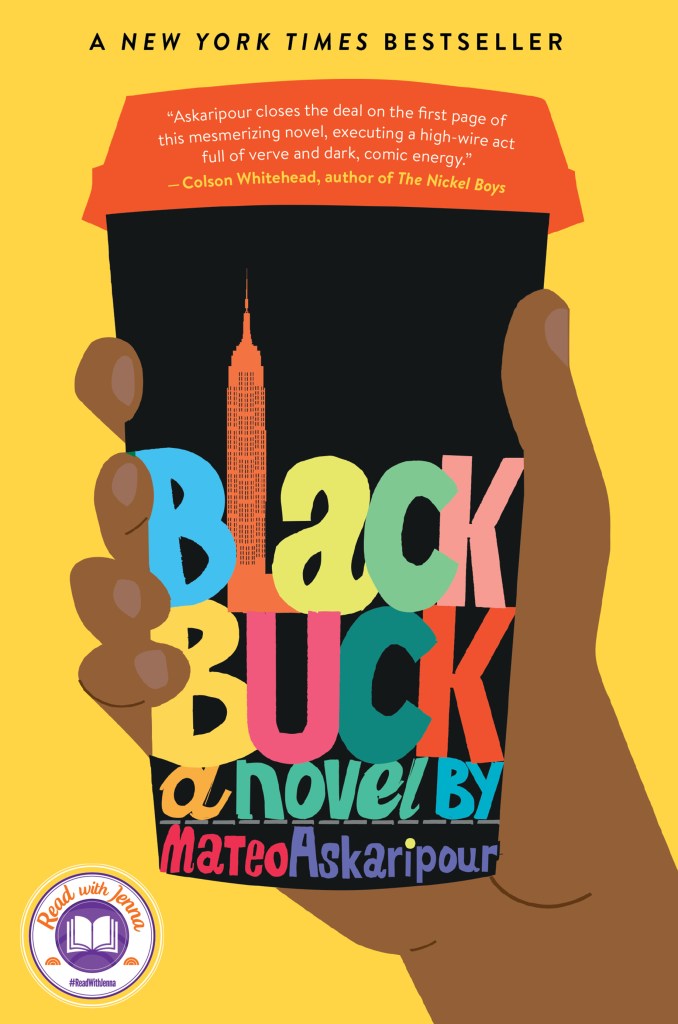

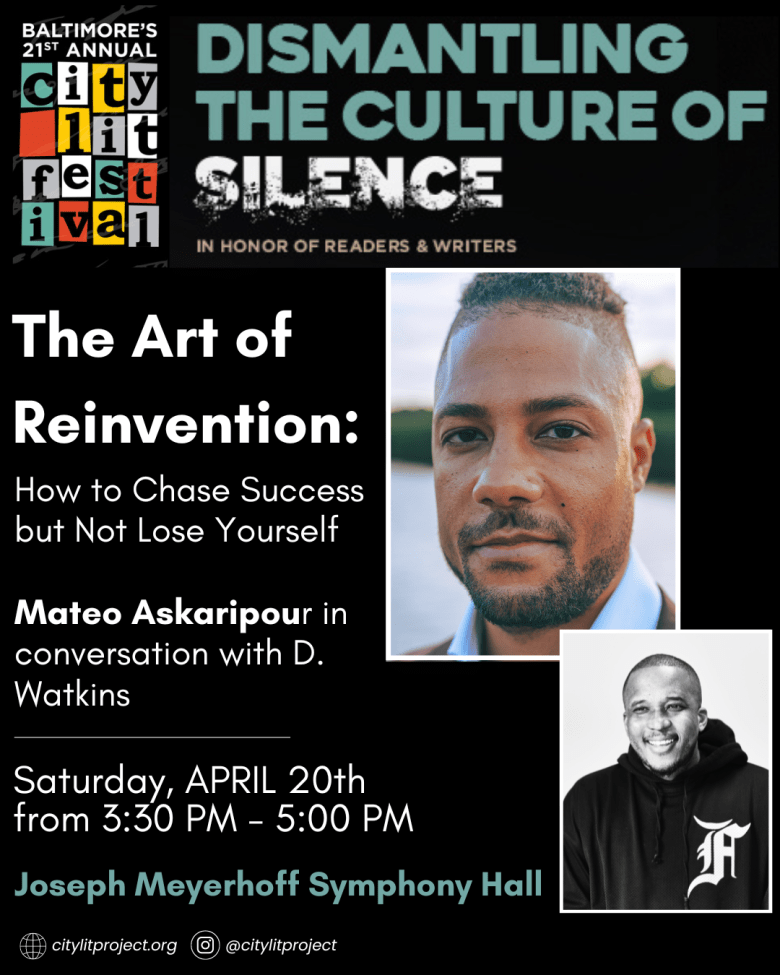

As Baltimore prepares for the 2024 CityLit Festival, writers and readers alike are glowing in anticipation of the literary marketplace. One of the many conversations on the horizon for Saturday, April 20, is between Baltimore’s D. Watkins and Mateo Askaripour, a Long Island native and author of “Black Buck,” his debut novel. The contemporary novel follows the rise of Darren Vender from barista to sales guru while chronicling the conflicts that begin to brew in every area of his life. Askaripour’s debut morphs New York City into a dramatic stage for readers to observe a fictional account of the real struggles between home life, work life and the quest for balance. Since the publication of “Black Buck” in 2021, Askaripour has written his second novel, “This Great Hemisphere,” which will be released this summer. Askaripour and I had the opportunity to chat on a sunny Sunday morning and explore the gratitude, spaces and characters that come alive for him in crafting his novels.

___

Bry Reed: I love book festivals because they allow us, as audiences in print literature, to engage with writers beyond the page. As you prepare for CityLit, what excites you most about engaging with readers at events like this?

Mateo Askaripour: First of all, it’s Baltimore. I’ve heard that people in Baltimore are a very special type of people, a very special type of audience that gives so much love and energy to artists. I’m honored to share space with D. Watkins. He’s the bard of Baltimore, and he’s someone who when I came into the game of literature and of publishing, I knew of him as a veteran. As someone who had come into this as himself and had never really switched up on those around him. I’m excited to share the stage with someone I admire greatly. And third, I’m excited to be in-person.

BR: Your debut novel, “Black Buck,” has received immense praise for its creative, satirical narrative about capitalism and labor. How did you come to write a satire as your first novel?

MA: When the book came out in 2021, I often found myself pushing back against that label of satire because I didn’t want it to be placed into this comfortable, convenient box. When I was writing “Black Buck,” I didn’t envision it purely as a satire. I knew that it had satirical elements. I knew that it had many absurdist elements, but I also felt that the narrative was incredibly grounded in what was happening and what was going on with the characters (internally and externally). And I also wasn’t envisioning one pure genre because I thought that that would limit the way that I would write the novel. It has elements of romance in there. It has elements, by the end, of a thriller, which was a surprise to me as I was writing it! With anything that I write, I try not to place it in a box because I feel that could limit my vision and limit how people could perceive it.

BR: In the way “Black Buck” is crafted, as a reader, I didn’t feel like I was moving through time. I felt like I was moving through space. There are different passages, and it feels like a traversing of New York as you’re traversing these relationships throughout the novel. Did any of your personal relationships influence the relationships and conflicts in the novel?

M: Without a doubt. Certainly some relationships came from relationships that I had. The relationship with Darren and Soraya is somewhat similar to a relationship that I had with the woman I was dating at the time. Certain workplace relationships — not all of them — but a few of them informed the narrative without a doubt. When I stepped into the world of startups, after a while, I had a mentor, and it was a very strong protégée, or mentor-mentee relationship, where I was learning a lot.

Some of the things that I’ve carried into my life today that were extremely helpful, and then some things that were a bit more harmful, and I had to unlearn after I left that space. […] What’s a joy is when people reach out and they say “You wrote about me and my life!” or “You wrote about me and situations that I’ve been in and it was difficult to read at times, but I knew I wasn’t alone.” To me, that is the highest manifestation of success.

BR: Absolutely. As you talk about the different relationships, one that really stuck out to me was the relationship between Darren and Jason from the start. As readers, we don’t get a lot of Jason’s POV of the changes and escalations that happen throughout the novel. Can you speak a little about crafting Jason’s POV?

MA: What did you think about Jason? Jason was a contentious character for a lot of people.

BR: You know who they made me think of? Song of Solomon. Milkman and Guitar. […] It’s class tension right? Those are the nuggets.

M: Darren and Jason — you nailed it on the head — these are two brothers. They’ve grown up in the same neighborhood but in different parts of the neighborhood. Darren lives in a brownstone that his family owns, and Jason grew up in the pjs, which is like literally a block away. Aside from that, I wanted to portray this extremely loving relationship between two men who love each other, but then a rift is presented when they go on two markedly different paths. We see the deterioration of their relationship, partially rooted in their inability to communicate. […] Jason feels like he can’t say “I’m hurt” or “You’re hurting me,” so it snowballs and becomes this tit-for-tat, negativity brewing and becoming almost malignant in the body. And it becomes blistering physical harm.

BR: When you talk about the four corners, I think about a compass.

M: Wow, wow, wow! In the three-and-a-half years since this book came out, I haven’t heard that.

BR: Really?

MA: Yeah, wow! When they’re fighting on the compass, it’s because they’ve lost direction — hard.

BR: I was thinking of it as a compass and a crossroads. They’re at the crossroads of so many relationships, and the neighborhood is at a crossroads.

M: And so much happens at that intersection. You see the gentrifiers, Soraya, her dad, Wally Cat, we see so much happening on those four corners. Which is representative of so many places. The drama isn’t taking place in a big auditorium on a stage. It’s taking place on a street on a curb on a sidewalk. And I think that when we think about the places we’ve grown up with — where we’ve been able to exist for a long time — they are their own movie sets with their own characters. And that’s exactly what I was looking to do with Bed-Stuy and Sumwun. And Bed-Stuy is different — it’s open air. But I had to create an entire world on an office floor. So what does that mean? It means that the different conference rooms had different qualities. All of these places were on the map of Sumwun.

BR: As you were crafting the novel, what spaces in our real literary world helped you bring these spaces to life?

MA: I’m thinking of multiple spaces. Literal, abstract, and so forth. Talking about the literal, I would go to readings in the city a lot. In Brooklyn, Manhattan. I would go just to see what it was like for these published authors to speak about their work and what it was like to interact with an audience. I would go to honestly siphon off a lot of inspiration for myself. Just seeing these artists at work. At times being able to ask a question or interact with them. I didn’t need anything else. It allowed me to touch and see something that was real. Even though my own dream was something that only existed in my spirit, that helped me immensely.

Being able to commune with these impactful writers every night [through reading] as I was writing this novel was also a safe and welcoming place where it felt as though I could be in conversation with [James] Baldwin, with [Toni] Morrison, with [Zora Neale] Hurston and with [Ann] Petry. With all of these people. With [Richard] Wright, with Chester Himes, with William Melvin Kelley. And then with contemporary writers, Nafissa Thompson-Spires, Mitchell S. Jackson, Brit Bennett, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. I was consuming so much art. And consuming it with a much more critical eye than I ever did before. […] Providence was the first place that I ever read any work and any work from “Black Buck.”

And I shared the stage with Jason Reynolds and a bunch of other talented authors. One being Carla Du Pree from CityLit.

BR: As you are in the space between the publication of the debut and the anticipation of the second, what are you holding on to in this space between those two? What is the bliss in this in-between?

M: I oscillate between [feeling like] the job’s not finished — Mamba and before him really MJ — and on to the next. In more than any other state of being, I’m in a state of gratitude. I am excited more than anything to hear what readers think. I’m proud of what I did and the various risks that I took in this undertaking because I could’ve just written a “Black Buck Two.” I am eager to take the lessons that I’ve learned in book two and put [them] into book three.

Mateo Askaripour’s latest novel, This Great Hemisphere, is available on July 9, 2024. He will be in conversation with D. Watkins at this year’s CityLit Festival on Saturday, April 20. Click here to learn more about the CityLit Festival.