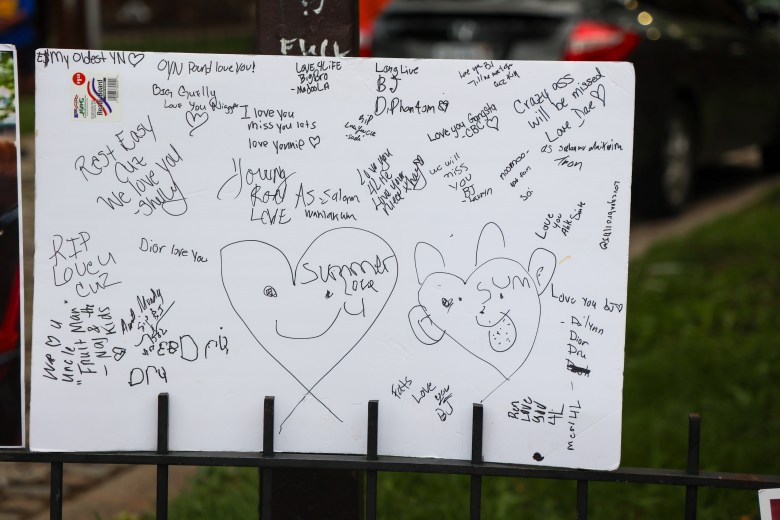

On the evening of the Juneteenth holiday, a crowd gathered near the Upton Metro station off Pennsylvania Avenue, not to celebrate the end of slavery in America but to mourn the shooting of beloved arabber Bilal Abdullah, known as BJ.

Tawanda Jones was standing where she has so many times since Baltimore Police officers killed her brother in 2013 — beside another grieving family. Joy Alston, the mother of Abdullah, was sitting in a chair, surrounded by her surviving children and other friends, family, and members of the community.

Alston was the only person sitting, but she was holding her head up, facing the crowd around her and the reality of what had happened, all while nursing an injured shoulder. When her son’s body was lying on the pavement, police physically wrestled her back as she was trying to reach him, causing the injury.

“I still was fighting to get over and see him on the ground,” Alston said. “When I finally got over, I saw him on the ground, and I knew he was dead. I knew he was dead then.”

“When you got men pushing you on and throwing you, doing all that at the same time, it’s hard,” Alston said. When her daughter demanded the officers leave Alston alone, they threatened to arrest her.

This is one of the reasons why, according to numerous people at the vigil, the crowd was so distressed on the night of the shooting. Not only did police officers shoot a beloved arabber, but as he lay there dying, they were not rendering aid and would not let his mother reach him, injuring her in the process.

“Everybody down here knows me and my kids,” Alston said.

Alston says that authorities kept the family waiting and in the dark at the hospital for over two hours.

“I said, ‘Where’s my son? I want to see him,’” Alston recalled. At first, doctors told her that Abdullah was in stable condition. The next thing they told her was that her son had died.

Exactly what happened is not clear yet, and body camera or other footage has not been released. After her daughter noticed a casing on the ground that police didn’t collect as evidence, Alston is concerned about how thorough the investigation will be.

The Maryland Attorney General’s Independent Investigations Division, which investigates police shootings, released a preliminary report describing the event:

“The preliminary investigation revealed that at approximately 7:15 p.m., Baltimore City Police Department (BPD) officers in an unmarked cruiser were in the area of Pennsylvania Avenue and Laurens Street when they encountered an adult man standing at the corner, carrying a crossbody bag on his back. The officers attempted to speak with the man from their vehicle, and then one officer exited the unmarked cruiser and approached the man on foot. The man began walking away and the officer followed. As the officer followed, the man shifted the bag from back to front and fled on foot.”

Illinois v. Wardlow ruled in 2000 that fleeing in a high crime area can provide an officer reasonable suspicion to make a stop — a ruling that was an important factor in the case of Freddie Gray’s 2015 death in police custody after he was chased for running in a “high crime area.”

But in the 2023 case of Tyrie Washington, who was standing with a friend in Baltimore City and ran away when approached by police and argued that after Freddie Gray, it was reasonable for a Black man to fear the police, even when innocent, the Maryland Supreme Court ruled that “unprovoked flight may occur for innocent reasons, including those associated with fear of police officers.”

“Courts and police officers make this mistake somewhat regularly,” said David Jaros, a professor of law at University of Baltimore. “They are mechanically assuming that simply as long as a suspect runs and they are in a high crime area that means necessarily they have the authority to pursue and seize them.”

“That’s not actually what the case says and it’s certainly not the kind of totality of the circumstances test that includes everything we’ve learned in the last 25 years about why an African American man might run from police,” he said.

According to the Washington ruling, there was no reason for what allegedly happened next to occur at all.

“A second officer exited the cruiser to assist. A third officer, posted at the intersection in a separate marked cruiser, also exited her vehicle,” the IID preliminary report says. “As the first officer grabbed the man, a firearm was discharged. This prompted the officers to retreat and/or take cover. The man then pointed a firearm at the officers and three officers exchanged gunfire with the man, striking him. A firearm was recovered from the man and secured by an officer.”

No evidence of Abdullah wielding a gun has been provided at this point.

No evidence of Abdullah wielding a gun has been provided at this point.

According to the IID, the shooting officers were “BPD Detective Devin Yancy, an 8-year veteran of the department; Detective Omar Rodriguez, a 6-year veteran of the department, both assigned to the Group Violence Unit; and Officer Ashley Negron, a 7-year veteran of the department, assigned to the Patrol Division.”

“Plainclothes” squads, which would include the Group Violence Unit and the District Action Teams, have had a deeply troubled history in the city, including the Gun Trace Task Force’s federal indictments in 2017.

Police scanner audio does not reveal how an officer was shot in the foot, but it is clear that, though a medic was called, that officer was transported to Shock Trauma in a police vehicle before Abdullah was transported by medic.

Though Commissioner Richard Worley seemed to blame the crowd in the aftermath, saying they “actually interfered with our ability to give the victim aid,” it is striking to members of Scan the Police, an abolitionist collective focused on monitoring police scanners, how seldom Abdullah is mentioned in the dispatch calls from either the Western or the Central Districts. “He’s only referenced once or twice in the hour or so of recording,” said a member of the collective, whose members do not want to be identified because of fear of reprisals.

“Cop down. Suspect was hit,” is one of the few mentions of Abdullah, shortly before the wounded officer arrives at Shock Trauma for care.

Much of police communication is encrypted, allegedly to ensure police safety, but with the convenient side effect of limiting scrutiny and transparency, and so it is impossible to know what else was said.

Communications with BPD’s aviation unit Foxtrot paint a different picture than Worley’s statement.

“Just to fill you all in. You got maybe a crowd of maybe 20-25 people. You got a lot of officers holding them back right now. We made an announcement for them to get back. [It] looks like they are starting to clear up right now,” Foxtrot said roughly seven minutes into the transmission about the incident. “We got plenty of officers. Way more than the people there.” Dozens of police cars were on the scene.

The Abdullah family has dealt with BPD misleading the public about their family before. In December 2022, Bilal Abdullah’s brother Zayne was awarded a $375,000 settlement for an altercation that occurred two years earlier. Initially, when body camera footage was released of people struggling with Police Sergeant Welton Simpson, police, politicians, and gullible news outlets jumped in to condemn the lawless behavior. “Just before midnight last night, one of our sergeants was conducting a business check on Pennsylvania Ave. when a person in the business became argumentative with the sergeant and spat in his face. Subsequently, as the video that was recently posted online shows, several other people began kicking the sergeant as he was trying to arrest the suspect,” then-Commissioner Michael Harrison said in a statement. Harrison said he was “outraged, as any resident of Baltimore should be,” and noted that “based on our preliminary review of the incident, the sergeant did nothing to provoke the assault, and the sergeant should be commended for using the appropriate amount of force to apprehend his assailant.”

Independent video revealed that Simpson bumped into Zayne Abdullah and said “get the fuck out of my face.” As they exchanged words, Simpson pushed Abdullah. Simpson was choking Abdullah and another man, who was also awarded a $375,000 settlement, tried to get Simpson off of Abdullah, who was saying he couldn’t breathe. Both men were held in pre-trial detention without bail until their lawyers released the new evidence. The incident occurred in the same neighborhood where Zayne’s brother, Bilal Abdullah was shot.

Several of Bilal’s siblings spoke at the vigil about how deeply Bilal cared about the people around him.

“He ‘gon put his heart on the line for anything,” said one brother, who didn’t want to give his name. “Everybody love him but his brother loves him the most.”

“He loved the kids. He loved the hood, everybody loved him,” said a sister. “Fruit man, everybody loved him.”

The family and supporters will be calling for justice in a protest that will meet at Penn North at 6 p.m. Friday June 20 and march to the Upton Metro Station.